Bill Mason grew up in Gulfport. He joined the Navy after high school, then attended The University of Southern Mississippi, from which he graduated in 1956. He’s been married 53 years. He and his wife have two children, now a stockbroker and a nurse.

Bill had always been interested in woodworking. He retired in Hattiesburg in 1993 following three decades in the field of banking. In casting about for ways to pass the time, he became intrigued by one of woodworking’s most difficult specialties, woodturning. He bought an inexpensive lathe and experimented. The first try was sobering: a piece of wood improperly placed on the cheap fixed-speed lathe shattered into two pieces that hit opposite walls of the shop! It taught him a lesson, and four or five hundred turned pieces later, there have been no serious accidents. After that first debacle, he decided to seek instruction. He attended a workshop on basic woodturning at the Arrowmont School of Arts and Crafts (Gatlinburg, Tennessee) led by master turner John Jordan, who has pieces on display in the Smithsonian and in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London. That gave him a good start, though he refined his technique over the years through reading books, experimenting, and simply honing basic skills meticulously.

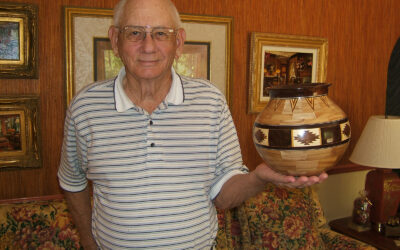

Bill now has a beautiful, spacious shop, with an excellent variable-speed lathe and other great tools. He used to travel quite a bit to exhibit his work at shows but has largely given that up. Now he makes pieces that please him, gifts, and the occasional commission (several local collectors each have over a dozen pieces by him). He has mentored several other fine woodturners. He still turns bowls of solid woods, working with woods ranging from readily available holly and black walnut to rare (and expensive!) materials such as, for example, rosewood burl from Belize and “pink ivory” (Berchemia zeyheri) from Africa. And smaller projects continue too, such as pens and peppermills. However, he has evolved into a master of a particularly tricky and time-consuming specialty, segmented vessels. In this technique, many small pieces of wood are cut very carefully so that they can be glued together in a ring. The first ring will be roughly turned, then other rings attached one at a time (from the bottom of the growing vessel up), with additional turning at each step, followed by refined turning (making the work as smooth inside as outside) and finishing, all still done with the piece on the lathe. Design is complicated since these pieces are essentially curved mosaics. It can take fifty or sixty hours spread over five or six weeks to finish an elaborate vessel.

In comparison, a carefully-made bowl from solid wood may take “only” ten or twelve hours. Bill finds it gratifying when somebody brags on a piece he’s made. He says it’s a good feeling when you know you’ve done quality work.