I arrive at Mr. Gipson’s place of residence at approximately 4 pm. Canterbury Crest is an assisted living facility; when I arrive, I notice two elderly African American gentlemen sitting outside, one of whom is in a wheelchair. As I approach them, I ask the man in the wheelchair if he is Mr. Gipson because I knew Mr. Gipson was confined to one at the moment due to an injury to his leg. He is not, and he directs me to where I may find him — room 104. As I enter the facility, I make a courtesy stop in the office to tell the lady on duty that I am there to see Mr. Gipson. She also directs me down the hall to his room, which is the second on the left.

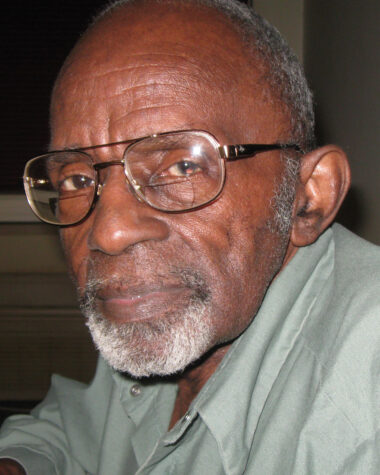

I knock on his door and he calls to me to enter. When I walk in, I am standing inside of a small kitchen area, with a refrigerator, stove, and sink to my left, and a small dining table directly in front of me. Mr. Gipson, a genial African American man in his sixties, is sitting in his wheelchair in the living room area, and graciously welcomes me. He is balding, with short salt-and-pepper hair crowning the top rear, sides, and back portions of his head; he also has a salt-and-pepper goatee. He wears thin-framed bifocals and a green work shirt. There is another elderly African American man in the kitchen area, whom Mr. Gipson introduces as Mr. Mitchell. I shake hands with them both, and Mr. Mitchell leaves — I believe he had come to Mr. Gipson’s room for some coffee, which Mr. Gipson says some of the people who live there will do as he makes it for them.

I sit down at the table, and Mr. Gipson and I begin to talk. I ask him how he is doing, as I knew he had suffered an injury in the weeks prior to my visit. He shows me the cast around his right leg and tells me that he is doing better but was in a great deal of pain. He speaks very highly of the doctor who is taking care of him.

We begin to talk about his artwork. He tells me that he has lately taken art classes through the University of Mississippi’s continuing education program, which he greatly enjoyed. They told him that to continue doing so, he would have to enroll in the degree program, which he said he didn’t want to do — he just wanted to paint, but apparently you cannot take the classes separately from the degree program. He says he has been creating artwork for 50 years or more; when he was in elementary and grade school, the teachers would ask him to do enlargements for them. He was especially encouraged in his artistic pursuits at St. Mary’s School in Holly Springs, where he is originally from. He was living at the Hollyview home there prior to moving to Canterbury Crest; he relocated to be able to take art classes from Ole Miss, and he is happy he chose to do so.

He attended Rust College for one year (’59-’60), majoring in social sciences. He would have liked to have majored in art, but it was not available to him at the time. He remembers fondly his art appreciation teacher at Rust, Ethel Waters, who gave him some instruction and encouragement. He mentions that he was also interested in music; he took piano for a semester while he was there and really enjoyed it but didn’t stick with it. He believes he might have made a good musician if he had.

Mr. Gipson begins to tell me about the paintings he has set out for me to view. There are three on the couch, one on the floor in front of the couch, another on the floor next to the TV, and an unfinished work on a table at the back of the living room, next to an easel. He mentions that he has called around town to different galleries to see how much it would cost to display his artwork; the Powerhouse said they would only charge him a third of the painting’s cost, I believe, while Southside would charge him half. He says he would rather start out displaying his paintings in a place like the Powerhouse, and perhaps work his way up from there. He talks about the PBS-TV artists Bob Ross and Helen Van Wyck and says that he liked them because they encouraged everyone to try their hand at creating art. He also mentions Chandra Williams to me, a local teaching artist on the MAC’s roster, and speaks highly of her.

The first painting we talk about is a pastel image of a pond framed on one side by a stand of what appears to be pine trees. He says this pond was on his family’s property when he was growing up. The use of pastels gives it an almost Impressionistic, soft-focus quality.

The next painting is a brightly-colored acrylic and portrays his grandfather’s red 1948 Chevrolet pickup truck. The truck is in the foreground, and behind it can be seen a pond, a stand of trees, and hills in the far distance — possibly the same pond as in the first painting, though I don’t ask him if this is so. The truck has a large, green bed on it, with high sides; he says his grandfather would use this to haul crops like cotton to town. It is signed by the artist in the lower left-hand corner and is dated “7-09” (July 2009).

Next is a pastel of a church in the lower right foreground of the canvas, and a brick building in the upper left rear. He says this was a country church and school in Slade, MS, that he attended when he was growing up. He talks about the plays, picnics, fish fries, and other events that the church and school would host, and how much he enjoyed going to them. He also mentions that the church was actually brick, not clapboard as it appears in his painting, and states that he altered it for personal aesthetic reasons.

On the floor in front of the couch is another painting of a church, this time in acrylic. The church is sitting in an open, green field, with an African American minister in the foreground, and parishioners on either side of the log-cabin house of worship. A cross serves as a steeple, and I don’t notice until Mr. Gipson points out to me that the roof is made of an open, black-covered Bible with yellow pages. He says that a minister who would come to Hollyview asked him to paint this specific image for him, down to the Bible-roofed church, but for some unknown reason never came to claim it.

I notice the acrylic painting on the floor to the left of his TV and ask him about it. Exclaiming that he had almost forgotten this one, he says that he painted this one to look like a Hawaiian volcano. There is what looks like an open, lava-filled crater in the center of the painting, with dark earth encircling it on all sides. A bright blue sky is overhead, and it is signed by him in the lower right foreground.

The final piece that he shows to me is lying on the table that is against the back wall of his living room. It is an unfinished work — in acrylic, I believe — and it will be of a bunch of roses when he finishes it, he tells me. The canvas is swathed in different shades of pink and red, and framed by the beginnings of green leaves.

I ask if I may take photographs of his paintings, and he gives me consent. As I do this, he repairs to his bathroom to take some medicine. I spend a few moments taking my portraits, and he returns to the living room as I am photographing the unfinished floral acrylic. He has some trouble getting his cast-encased foot on the wheelchair pedal, and I offer him assistance by pulling the pedal up so he can lift his leg, and then put it back down for him to rest his foot on.

We sit and chat amiably for a while longer. Among our topics of discussion are his family, and his Catholicism. He was raised Protestant but was inspired to convert after attending the St. Mary’s School; he appreciated how caring and supportive they were of him. He also says repeatedly that he wants to get busy pursuing his artwork again; I don’t ask him why he stopped, but I am assuming it is due to his recent illness and injury. At one point, I ask if I may take his portrait, which he also agrees to after a moment’s hesitation. I tell him repeatedly that I won’t do so if he doesn’t want me to, but he says it’s all right and I take a few pictures. I show them to him, along with the ones I took of his paintings, and he is pleased with them all. At another point, there is a knock on the door, and he calls to the person to enter. It is another resident, an elderly African American male with a long white beard, wearing a cap. Mr. Gibson calls to the man to come on in, but his friend declines to enter after seeing me there. Mr. Gibson says after the man leaves that he is shy, and was probably looking for some coffee, as he makes it for any of the residents who want it. He talks about how much he likes coffee and says that he should have offered me some. I tell him I drink a little bit, but not very much as it agitates me. He says that he got another resident hooked on drinking coffee the way he makes it. He also mentions that he wishes he could stop smoking and that he wished he hadn’t picked up the habit as a young man. I noticed the moment I came in that the room smelled strongly of cigarette smoke, and by now I have a terrible headache, but I do not mention this to him.

He talks about the Rosenwald public school that he attended as a child, and says that when he was 11, he sent in a drawing to a magazine correspondence course contest. They gave him a C, he said, but could not accept him because he wasn’t 17 years of age; nevertheless, he was proud of the grade he made. He says that other images he would like to paint are wagons, cotton fields, mules, and cows — memories from his childhood. He would also like to try his hand more at florals, and at portraiture. He likes to paint either late at night or early in the morning when it’s quiet at Canterbury Crest. He really enjoys painting pictures of bygone times and mentions that he would love to be in the Smithsonian someday. I tell him the story of Ethel Wright Mohamed of Belzoni and her “memory pictures,” and say that since she was able to make it there, it’s not impossible for him.

After a bit, we say our goodbyes and wish each other happy holidays. I depart Canterbury Crest for my home in west Oxford at approximately 6 pm.

– Melanie Young