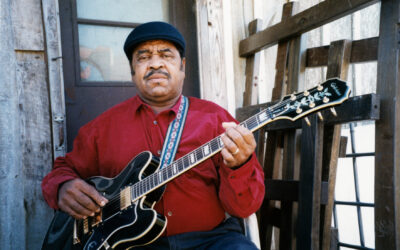

Elmore Williams lives with his wife in a comfortable home in the suburbs of Natchez and is retired after years of working in sawmills, a bakery, and a dairy. Although he’s played music for nearly sixty years, Williams only spent about two years working full-time as a musician, and today he mostly plays at festivals, often far from home.

Although Williams began performing in Europe already in the 1980s, he first gained broader acclaim following the release in 1998 of a CD on Fat Possum that he shared [as “Elmo” Williams] with Hezekiah Early, Takes One To Know One. In the wake of the CD, the pair traveled across the U.S. and to countries including Finland, Sweden, Portugal, and Japan, and Williams recently traveled on his own to perform in Italy.

He was born Elmore Williams, Jr., in Natchez on February 6, 1933, and lived in Fenwick, just east of the city, until he was eleven when his family moved back to town. His father was a blues guitarist who worked as a cement finisher and was killed while traveling to work in Biloxi. Elmore was just ten at the time and regrets that his father was not able to teach him about music.

“I was supposed to learn from him to play the blues, but he never did get a chance to teach me. So, I learned what I could find out on my own, I just tuned it where I could play something. I didn’t care how nobody else they tune their box, I tuned mine the way I could play it.”

Williams has particularly rich memories of the wide variety of music found in Natchez from his childhood.

“The businesses were mostly on St. Catherine Street, you had cafes and juke joints all the way up the street. You could come up St. Catherine and just about every joint you’d find somebody with a guitar. They’d be in their playing, at least on Fridays and Saturdays, and on Sundays they’d have a few joints open, but the rest of the people would be going to churches up and down St. Catherine.

“There was Cat Iron [William Carradine] and “Tucker,” and there were two or three more. They never would never teach you nothin’, they were jealous, I think, [that] you were going to cut their throat. And my mama’s first cousin, he wasn’t with the blues, but he had a band, Otis Smith. They played down in Crowley, LA for about twenty some years. They had an upright bass, saxophones, trombones, and trumpets.

“Papa George [Lightfoot], he lived down the street from the alley I came up in, down on St. Catherine Street. I know the spot where his daddy’s house was, right on East Franklin there. He was a hustler, he had a snowball wagon, he sold peanuts. He would blow his harp while selling, and he would make some change from that as well.

“That Papa George was something, he was full of fun. He would clown, he’d blow his harp and put two sticks between his fingers and that’s how he kept time. You’d hear that “clack, clack” in rhythm with his harp playing. He had wooden slats, they looked like rulers. He was a professional musician, ‘cause he played with [bandleader and national radio show host] Horace Heidt, while Horace Heidt was here. Horace Heidt wanted him to follow the band, but Papa George never did go with him.”

He also recalls seeing local African American fife and drum groups performing both in town and at rural picnics.

“You could see that sometimes on St. Catherine, some of them cats would get together and them fife and drums get to boogien’ down. Yes, indeed, back in them times you had Al Miller, he had a group, Otis Jackson, he had a group—them are the two groups I remember good. [They had a] snare and a bass and a fife. They played for picnics or anywhere they could play. Everybody went to one of those.”

One of Williams’ most vivid memories from his childhood is of the Rhythm Club fire.

“I was young when that burnt down. I went with my dad up to look at it, and I looked at all the dead bodies piled all up and everything else that next morning.”

On the Fat Possum CD Williams performs a song that closely follows Howlin’ Wolf’s “Natchez Burnin’.”

“I’ve been singing all the time about it, but I’ve been putting new words to it, I changed it ‘round. I play it near about every night when I go play.”

Williams first began performing at local gatherings as a teenager together fellow guitarist Chris “CP” Proby, but their partnership was interrupted when he was drafted into the Army.

He did so together with a friend, Chris “CP” Proby, and they began performing together at gatherings in the area in their teens. In 1952 Williams was drafted into the Army but did not have to go to Korea, serving instead at Camp Pickett in Virginia.

After Williams was discharged from the Army he returned to Natchez, where he sang with a band led by John Fitzgerald that also featured guitarist James Woods and drummer Hezekiah Early. They often performed at Haney’s Big House in Ferriday, Louisiana, which was the biggest club in the region. Groups that Williams recalls seeing there include Fats Domino, B.B. King, Junior Parker, Bobby “Blue” Bland, Smiley Lewis, and Lloyd Price.

In the mid-‘50s Williams formed his own band, which played at Natchez area venues including the Horseshoe Club, Dan’s Hot Spot in Jonesville, LA, and in Ferriday at Haney’s, Will Smith’s and Robert’s Casino [owned by Robert Wilkerson]. All three of these clubs were on the same block and were destroyed in a 1966 fire that all but ended Ferriday’s African American nightlife scene.

Williams also performed for white audiences at the area with his own group and with a trio consisting of himself, trombonist Leon “Pee Wee” Whittaker, and drummer “Happy Jack.” He recalls that white audiences enjoyed blues—he has long enjoyed performing songs by artists including B.B. King, Muddy Waters, Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown, and T-Bone Walker—but that they also liked “sentimental” songs by the likes of Nat King Cole and Ivory Joe Hunter.

Other differences he notes are that white clubs tended to have earlier hours [Haney’s, he says, ran from “kin to cain’t’] and paid better in salary and tips. Whereas musicians had to buy their drinks at black clubs, he says that when playing white clubs, he could always get free drinks by singing a song with the lyric “I am dry, bring me something wet.”

In the ‘70s and ‘80s, Williams performed largely at events including weddings and various informal get-togethers. In 1984 he performed several shows at the World’s Fair in New Orleans, and in November of that year, he traveled to the Netherlands to perform at the Blues Estafette festival in Utrecht, which also featured Mississippi artists including R.L. Burnside, Johnny Woods, and Hezekiah and the Houserockers.

Williams says that he often performed at juke joints in Natchez until the advent of riverboat gambling in the early ‘90s. Prior to this, he explains, club owners could afford to pay musicians with the money they made from selling bootleg liquor and their take from backroom gambling games. “The boat [casino] cut all that out,” he says, and with their arrival, he largely left music.

With the exception of about two years when he played music full-time Williams always had day jobs, working in sawmills, a bakery, and a dairy. He returned to active performing in the late ‘90s after the owners of Oxford’s Fat Possum Records tracked him down and recorded him together with drummer/vocalist/harmonica player Hezekiah Early. In 1998 Fat Possum issued the CD Takes One To Know One (by Elmo Williams and Hezekiah Early); other songs from those sessions were issued by the label in 2008 on the vinyl-only EP American Made.

Following the release of the CD Williams and Early toured across the U.S., traveled to Japan, and made multiple visits to Europe. Williams occasionally plays at a festival in Mississippi, and in the 2000s performed several times at the Deep Blues Festival in Minnesota. In 2010 he returned to Europe with Hezekiah Early to perform at a festival in Italy.