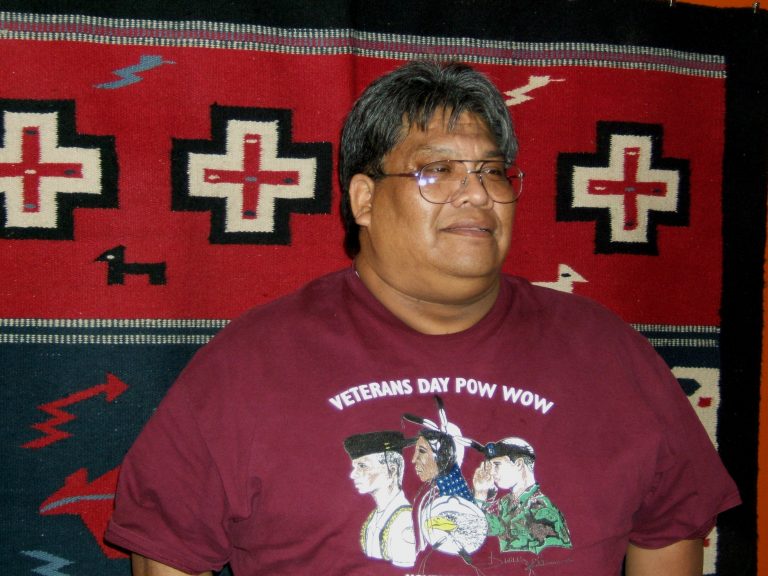

Harold “Doc” Comby, a member of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians, was born and raised on the Choctaw Reservation near Philadelphia, Mississippi, where he lives today. He has a degree in social work from Jackson State University and has taken graduate courses in vocational counseling at the University of Southern Mississippi. He first worked as a youth counselor on the reservation, has been a substitute teacher in Tahlequah, Oklahoma, and has spent over a quarter of a century as a police officer, first with the Bureau of Indian Affairs, working in Louisiana and Minnesota, and, since 1991, back home in Mississippi, where he is currently Captain of Operations on the Choctaw Reservation police force.

Comby was raised in a traditional way, following Native American teachings, which emphasize respect for oneself and for others, and for life in general. When he returned to Mississippi from his time working in Minnesota, his mother sat him down and went over the old stories and traditions very carefully and many times. She was delegating the function of tradition bearer to him, transferring both her abilities and repertoire.

Comby says that his mother didn’t tell funny stories, but rather told stories in a funny way. He’s not sure if any of his four daughters will carry on the tradition. He tells the stories at powwows, school programs, and for church groups. Many of his stories explain how things came to be. One of them describes how the possum once had a bushy tail but saw that the fox squirrel’s tail was even bushier. The possum sought the squirrel’s advice on how to reach that level of bushiness and was told to put his tail in the embers of a fire . . . which singed off all the hair. Another of his stories explains the extreme curviness of a stream in the Choctaw community of Conehatta—a big snake made those, one still alive somewhere in the swamps.

In another traditional realm, Harold makes stickball sticks and balls. Stickball may not be as ceremonial as it used to be, but it’s just as rough, he points out. It’s still an active tradition among Choctaw people.

Comby got his start as a powwow emcee when he filled in at the last minute for someone who had become ill. He currently emcees at six or more powwows every year, primarily in Mississippi, but ranges from Georgia to Louisiana on occasion. His main responsibility is to keep the flow of the event going. This has to be done in a way that respects the traditions of the different tribes involved in a given powwow, but also maintaining a comfortable but proper atmosphere. This requires Comby to have meticulous knowledge of the different traditions and be able to exercise considerable diplomacy—in fact, calling on many of the same skills he uses as a police officer.

Comby enjoys the perks of being emcee, the free food, and expense money, but often volunteers his services due to the social and spiritual value of powwows. He notes that involvement in powwows helped him through a difficult period in his life. He likes to get kids involved in powwows because they are helped in that environment to learn how to be good people, to have more self-esteem, and simply to know who they are.

– Chris Goertzen