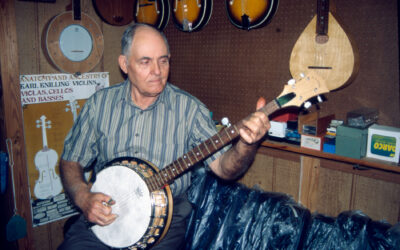

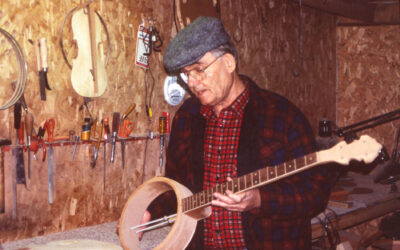

Master instrument builder M. B. Green was born in Soso (Jones County) in 1930, into a family of farmers. When his father died in 1945, the family moved to be around his mother’s relatives in nearby Louin. He married in 1951 and his family would eventually include six children. He worked as a baker (including in the Army during the Korean War), a barber, then, for 35 years, rebuilding Conn organ tone generators, plus repairing these and other electronics. When he retired in 1992, he had already been running his Banjo Shop on his own land for a dozen years, selling both his own instruments and inexpensive imports.

Green bought a Kay banjo from Sears in 1960. During the 1970s, then again in the 1990s, he played in a bluegrass gospel group. He was interested in how his banjo was made, so he measured it carefully and duplicated it to the best of his ability. He stored the new instrument under his bed. After a while, somebody that knew he played asked if he knew where they could buy a banjo: they were hard to find. So, Green’s first banjo changed hands, and he cautiously made two more. They both sold quickly, and he has not looked back.

He wishes he had kept track of his production more carefully. Green estimates that he has built about 300 banjos, 150 guitars and mandolins, a handful of dobroes and steel guitars, a lute, and, most recently, nine harps. He’s also built an upright bass, several washtub basses more elaborate than the norm (they have an actual soundboard and four strings), plus more experimental projects such as a gourd banjo, a banjo with a wooden face (for quiet practice), a mandolin made to look like a fiddle, and a bouzouki (he had seen one on the Grand Ole Opry).

Most of Green’s banjos are made largely of sycamore, a wood that is traditionally associated with violin making. He has quite a pile of this and other woods air-drying outside of his shop, while a colorful array of tools and partly finished instruments fill the interior. While he is a very careful builder, he is also adventurous, mixing replication and improvisation freely. For example, his first harp was louder than the one lent him as a model. This was because when he couldn’t find the usual nylon sleeves for where the strings pass through the soundboard, he employed aluminum rivets instead, which let the strings ring more freely.

When he is making an instrument, Green can “forget about everything and concentrate on just doing that.” It’s helped him in focusing mentally, in building patience; he says it’s been “a joy and a blessing.” Making instruments also disrupts family life less than his playing had—he was banished to the storm cellar when he was learning to play the banjo and when his band practiced. Now he spends most of most days making or selling instruments. Business can be brisk or can be sparse, but he doesn’t “let many customers get away.”

-Chris Goertzen